Smartphones: How Did We Get Here?

Article By : Junko Yoshida

In fall 1995 camera phones made their little-noted debut on the global stage. The combination was an unthinkable marriage of two disparate products

EE Times, in the first week of November, 2015, posted the following story to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the announcement of the first camera phone at Telecom 95 in Geneva.

The camera phone was a harbinger of the mobile phone’s epidemic future, leading eventually to smartphones with remarkable Swiss-Army-knife-like mutations. Little did we know then, though, how the camera phone would evolve.

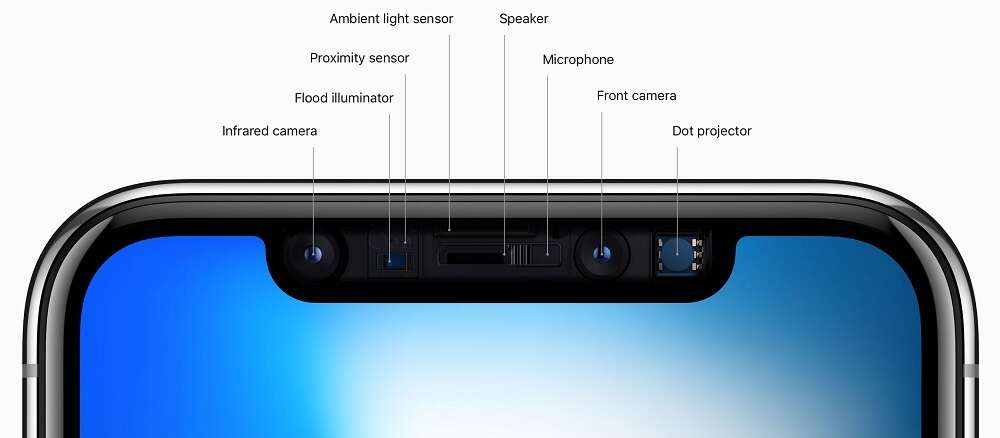

Since we published this story four years ago, the smartphone became a full-fledged and fully connected sensor hub in your hand. The gizmos inside the smartphone include not just image sensors, accelerometers, GPS, a gyroscope and magnetometer, but also proximity and ambient light sensors, microphones, touch screen and fingerprint sensors, a pedometer, QR Code sensors, barometer and heart rate sensors. The latest Google Pixel 4 smartphone even comes with Infineon’s radar chip.

These sensors enable functions that range from facial ID and speech recognition, to cab-hailing, car-locking, house-watching, health monitoring, package delivery and summoning your car the way Roy Rogers used to call Trigger. All these tricks happen simply with a touch of (or a voice command to or a gesture at) the mobile device.

And let’s not forget: following the pioneer footsteps of the camera phone, smart phones are also making huge advancements in imaging. As demonstrated in Apple’s iPhone 11 Pro and Pro Max — both featuring a triple-lens 12MP rear camera array, nowadays smartphones are capable of capturing high-resolution video, produce professional-quality still images, playing back 4K video on your palm and enabling AR and VR.

QED!

*************************************************************

MADISON, Wis. — Today, a smartphone without a camera is unthinkable. Twenty years ago, this combination would have been an unthinkable marriage of two disparate products without an industry interested in developing it.

Camera phones made their little-noted debut on the global stage in the fall of 1995 during Telecom 95 in Geneva.

At that conference, Japan’s Matsushita (Panasonic) unveiled a camera phone that made no headlines. The device failed to crack the website of the conference’s organizer, the International Communication Union (ITU) community, recalled Jacques Kauffmann, an independent imaging-technology consultant, and president of Imaging Management & Communications in Wilmette, Ill.

The telecommunications industry then had little idea how imaging (and video) would forever change data traffic and cellular network infrastructure.

Vice versa, the imaging industry never dreamed then how cellular phones would eventually eat their business alive by decimating the market for standalone consumer cameras. Of course, “back then [in 1995], no one from the imaging industry was attending telecommunications events,” said Kauffmann.

By melding two technologies and industrial sectors – imaging and communications — camera phones brought profound changes to businesses, markets and consumers that few saw coming.

Asked about the results of the camera phone phenomenon, 20 years later, Richard Doherty, research director of Envisioneering Group, pointed out: “the runaway success of the selfie,” “the death of privacy” and the impact on the industry which “changed the cost of imagers forever, accelerated CMOS imaging form what was only CCD to begin with.”

For decades, investors, marketing and engineering executives preached the gospel of “convergence,” “disruptive technologies” and “game-changing” applications. However, most of these preachers – media included – have proven terrible at predicting such disruptions, or even recognizing a “game-changer” while watching the game.

Typically, the experts in any given industry or technical field are reluctant to climb down from their personal soapboxes to examine the potential value of a new product category they’ve never seen. For the imaging industry, devoted to the improvement of imaging, the poor picture quality generated by camera phones made it almost impossible for them to take them seriously.

Kauffmann personally called Matsushita’s prototype a “camera phone.” He told us, “While I myself found this ‘new’ device revolutionary and promising, some imaging industry leaders I talked to didn’t agree. A ‘gadget’ was a common comment I heard. In a way, it reminded me of similar comments made in the second half of the 1980’s when single-use cameras [disposable cameras] were introduced.”

In contrast to experts, however, consumers almost instinctively embraced the utility of a camera phone. They understood the cliché: “The best camera is the one you have in your hand.”

The camera phone revolution is hardly over today. The megapixels race is shifting, as the camera phone becoming more a “sensing,” rather than “imaging” device.

In the following pages, we chronicle how camera phones brought unimaginable changes to markets, consumers and society at large.

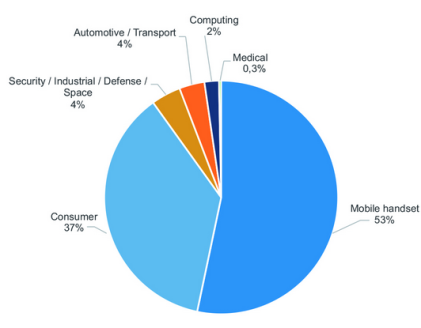

(Source:CMOS Image Sensor Report by Yole Développement, Jan., 2014)

Panasonic PHS Camera Phone at Telecom ‘95

At Telecom 95, whose theme then was “Connect!,” held Oct. 3-11 1995 in Geneva, Switzerland, “I saw in a corner of the Panasonic booth an engineer showing the prototype (shown above), to rare visitors who were showing an interest,” explained Jacques Kauffmann. “Back then, not too many members of the telecom industry had any interest in imaging-centered products.”

The product – a mobile phone integrated with a camera – seemed to have captured little attention among attendees.

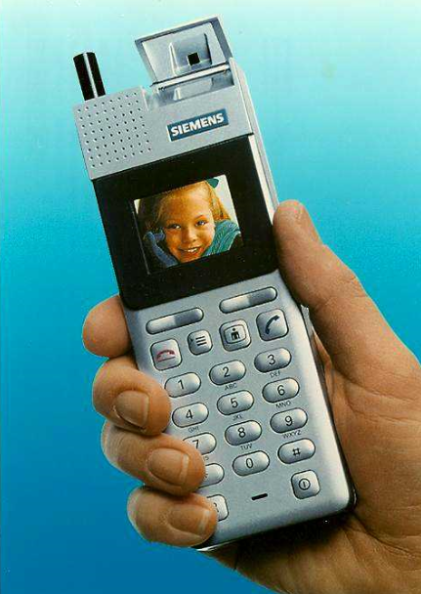

Matsushita’s first camera phone, however, did not entirely escape other vendors’ notice. “A few years later, at CeBIT ’98 in Hannover, Germany, Siemens had this device on display,” said Kauffmann. “This was called by some a web camera,” he added.

By Telecom 99 (Oct. 10-17 1999) in Geneva, Switzerland, billed by conference organizer ITU as “The Internet goes mobile,” a handful of companies were by then showing camera phones, some already with two cameras back-to-back, a design adopted soon afterward by DSC/digital still camera manufacturers, explained Kauffmann.

Philippe Kahn

The Silicon Valley crowd might argue the most celebrated camera phone moment came not from Panasonic but from Philippe Kahn. It’s now well-known that Kahn, a technology innovator and entrepreneur took the first image of his newborn baby in 1997 and instantly shared it with more than 2,000 people around the world from the maternity ward. He used his own wireless sharing software and a camera integrated into his cell phone.

Kahn’s contribution to the camera phone lies in the development of “Sha-Mail” (“sha” means image-capture in Japanese) software and infrastructure, which allowed Sharp to offer camera phones that could instantly share pictures.

First Commercial Camera Phone

(photo taken by Morio)

Sharp was the first company to launch a commercially available camera phone in 2000. The camera phone, released by J-Mobile (now, SoftBank) in Japan, offered 0.1 Megapixel resolution.

The phone, dubbed J-SH04, came with an integrated CCD sensor, with the Sha-Mail infrastructure.

Sha-Mail and Multimedia Messaging Services (MMS) were developed parallel to and in competition to open Internet-based mobile communication provided by GPRS (and later 3G networks).

Kauffmann recalls that countries such as Japan and [South] Korea jumped on the [camera phone] bandwagon quickly. “By the early 2000s, I was able to exchange images with a friend of mine from the floor of Japan’s CEATEC, at Tokyo’s Makuhari Messe. He was using a camera phone on the KDDI network, mine was on NTT DoCoMo’s network,” he said.

Meanwhile, in the United States, the camera phone revolution took much longer, due in part to an alleged lack of interoperability between devices on leading carriers, added Kauffmann. Early adopters of camera phones in the United States were essentially held captive by proprietary MMS business models.

The first commercial deployment in North America of camera phones was in 2004. Sprint wireless carriers deployed some one million camera phones manufactured by Sanyo and launched through a Sha-Mail infrastructure developed and managed by Philippe Kahn’s venture, LightSurf.

Mega-Pixel Battle

(Source: Nokia)

The mega-pixel war in the digital still camera market quickly moved its battleground to camera phones.

Nokia took the camera phone phenomenon to heart, becoming one of the most aggressive mobile phone companies to go after the consumer camera market.

After rolling out in 2002 the Nokia 7650, the company’s first camera phone with a 0.3 megapixel sensor, the Finnish mobile giant launched by 2005 a mobile phone, the N90, featuring a 2-Megapixel camera with Carl Zeiss lens, flash, a video camera style swivel and double screens.

By 2010, Nokia had its N8, a touchscreen-based smartphone running Symbian OS, featuring a 12-megapixel camera, supporting 3.5G radio network in addition to an HDMI output, USB-On-The-Go and Wi-Fi 802.11 connectivity.

The Digital Camera in Free-Fall

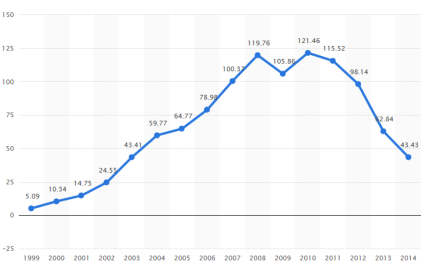

(Source: Camera & Imaging Products Association)

CIPA member companies – mostly Japanese camera vendors – shipped 5.09 million digital cameras in 1999. By 2010, the number of cameras shipped had increased to more than 121 million units.

If the market stats generated by CIPA are any indication, the digital still camera market – including SLR cameras – is now in free-fall.

Now that a growing population of first-time buyers of digital still cameras (DSC) in the emerging market is increasingly choosing smartphones over DSC, this is understandable.

A closer look at the CIPA’s data also suggests that even the single-lens reflex camera market, which peaked at 20 million units in 2012, is also going downhill. Shipments of SLR cameras in 2014 were 13.8 million units.

Selfie Boom

(Photo: Junko Yoshida)

By the late 1990’s, Kauffmann says vendors were already looking into integrating a camera — one in front, one in back, but it took until the fourth quarter of 2003 for the first commercial selfie mobile phone to hit the market.

Sony Ericsson’s Z1010 was a mobile phone with a front-facing camera with 0.3 megapixels sensor for selfie and video call.

Of course, back then, the word “selfie” wasn’t used to describe that camera.

It took until 2012 for “selfie” to become one of the buzzwords of the year.

It should come as no surprise that, to some consumers, the images taken with the front camera are as important as those from the “main” camera in the back to some people.

(Source: HTC)

In 2015, HTC joined other smartphone vendors to launch the extreme selfie camera, called the Desire Eye, featuring 13-megapixel cameras on both the back and the front.

Privacy Gone Forever

(Source: Post and Courier)

Having a mobile phone capable of taking pictures at the moment’s notice has brought dramatic changes in the way people see the world events (disasters captured by camera phones as they unfold) and they seek evidence for social justices (police brutality, street fights, political campaign trails, etc. caught by camera phones).

Gone big time is privacy. Literally, billions of camera phones in the hands of large populations made no place to hide for not just celebrities but ordinary people.

Envisioneering Group’s Doherty said, when he first saw the camera phone, “I immediately thought individual privacy was now gone. I was right. In Japan of course, using a camera phone was accompanied by a clicking shutter sound. Not so in other countries.”

Camera Phone as a Sensing Device

If smartphone vendors insist on sticking to the mega-pixel CMOS image sensor battle for their camera phones, they could run the risk of missing emerging applications in which a camera phone is used as an interactive computer vision device.

One example is the use of a camera phone to scan QR Codes. A phone can sense QR Codes using its camera and provide a link to related digital content, usually a URL.

The growing computing power in a smartphone is also making it possible to shift the camera phone’s focus from image capturing to vision processing. Instead of racing for more mega pixels, some applications are now looking for how fast and how accurately a processor in the smartphone can capture, dissect, and interpret data in a manner comprehensible to smartphones.

Consider the use of smartphone as breathalyzers. The application appeared first on the market in 2012.

BreathalEyes determines blood alcohol content using an iPhone. BreathalEyes scans the user’s eyes to measure the presence of Horizontal Gaze Nystagmus (HGN) — an involuntary jerking or bouncing of the eyeball. For this iPhone-turned-breathalyzer, all you need is an iPhone camera and a 99-cent BreathalEyes app.

Augmented reality (AR) also promises to be fertile ground for smartphones. Take an example of AR browser. The browser uses the mobile phone’s sensor data (i.e. camera, GPS, digital compass, etc.) to identify the user’s location and field of view. By using the geographical position, various layers of data can be inserted over the camera view.