Microchip Combats the CPU/Memory Bottleneck

Article By : Gary Hilson

Microchip is entering the memory infrastructure market with OMI-based serial memory controller.

TORONTO — Microchip chose to enter the memory infrastructure market at the Flash Memory Summit with the introduction its SMC 1008, a serial memory controller designed to alleviate the bottleneck between the CPU and memory.

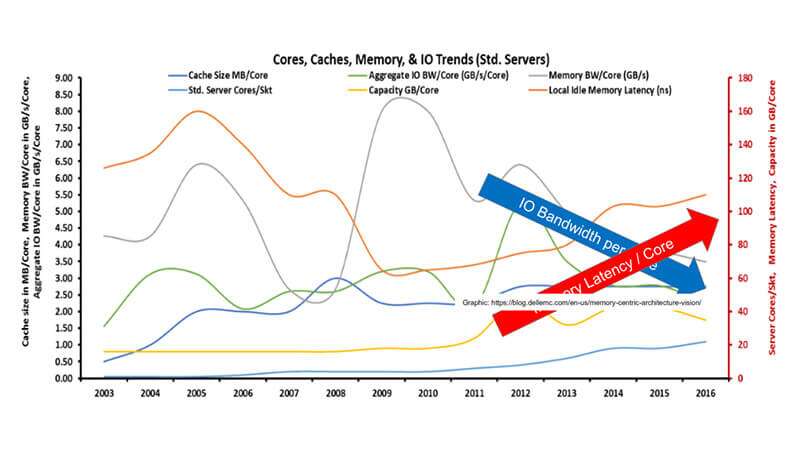

Microchip’s SMC 1000 8x25G enables CPUs and other compute-centric SoCs to use four times the memory channels of parallel attached DDR4 DRAM within the same package footprint, according to product marketing manager Jay Bennett in a telephone interview with EE Times. From a CPU point of view, the number of embedded cores has been steadily increasing, but the memory bandwidth capability of that CPU has not been keeping pace. “Individual cores within the CPU are each individually experiencing a decrease in aggregate bandwidth and also an aggregate increase in the latency for each of their individual transactions,” he said.

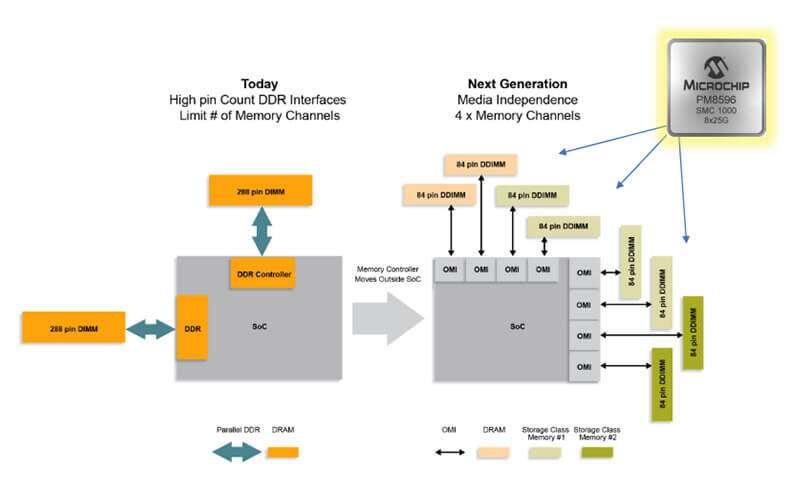

The problem is being compounded by changing and increasingly demanding workloads, said Bennett, and the key objective of the SMC 1008 is to increase available memory bandwidth. It interfaces to the CPU via 8-bit Open Memory Interface (OMI)-compliant 25 Gbps lanes and bridges to memory via a 72-bit DDR4 3200 interface. This reduces the number of host CPU or SoC pins per DDR4 memory channel, which allows for more memory channels and increasing the memory bandwidth available.

Citing Dell-EMC research, Microchip said current processor DRAM buses are limited in number and have limited performance scaling and multi-core processor devices are experiencing increased latency per core. (Source: Microchip)

Emerging workload demands means it’s no longer feasible to use legacy interfaces such as PCIe, SAS, or SATA, according to Bennett. “Those interfaces are too inefficient. That’s why these new interconnects are required.” Microchip has opted to use the OMI standard — championed by IBM, AMD, and Google, among others — on one side of the device, while the other side of the device is a 72-bit DDR 4 interface. “It is a broad specification, has a lot of coherent commands, and is a very rich protocol.”

Using OMI will enable customers to take advantage of a broader ecosystem and not get locked into a single solution, said Bennett, which allows for other memories to be used, whether it’s DDR5 when it hits the market, or other storage-class memories. “The door is open for additional innovation with storage class media of whatever flavor,” he added. Because OMI is significantly more pin efficient and the IP is available on a royalty-free basis at no cost, he said, the result is reduced silicon die, IP, and packaging costs.

Dennis Hahn, IHS Markit’s principal analyst for data center storage, said Microchip is right to focus on what is a pretty significant problem — how to get more bandwidth coming out of a CPU to the memory without exploding the pin count on the CPU package. “By using a serial link instead of a parallel link like what is used for DDR today, they’re allowing you to use a lot less pins.” He said it’s important that any solution affecting DDR access doesn’t add significant latency. “It cancels the whole benefit you’re getting by serializing for higher bandwidth.”

Microchip said its SMC 1000 8x25G increases memory bandwidth by four times. (Source: Microchip)

Hahn said the problem is something many vendors are working on as artificial intelligence and machine learning continue to increase their performance demands and want to use more memory. “There’s a memory bottleneck created by the need from some of these really high-performance applications to access more memory at higher speeds.” He said Microchip’s approach, as well as the general idea of serializing access to DDR, is a good solution, but there will also be interest as to how storage class memories might fit it.

Other “serializing” efforts include Gen-Z, a consortium collaborating on an open “memory-semantic” protocol that’s not limited by the memory controller of a CPU for use in a switched fabric or point-to-point where each device connects using a standard connector. Another consortium-driven initiative is Compute Express Link, that aims to be an extra-fast interconnect between CPUs and accelerators in the data center.

Intel is part of the latter, and Hahn notes it often has a significant influence on what solutions become the industry standard. Microchip is depending on OMI getting traction, and the fact that IBM has chosen does bode well. “Right now, I don’t think anyone quite knows how big this market will be.”