Debunking wire wrapping’s presumed unreliability

Article By : Bill Schweber

Learning to do wire wrap has taught engineer Bill Schweber not to assume what would and what wouldn't work well.

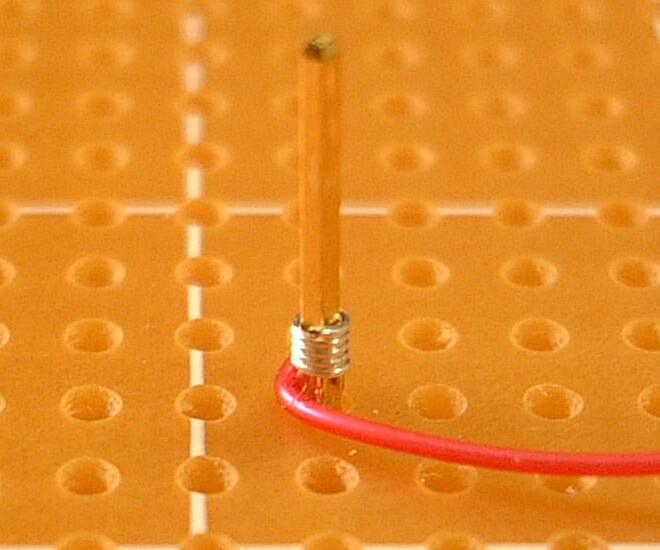

Many years ago, in one of my first real engineering jobs, I encountered "wire wrap" as a technique for doing interconnects on both prototypes and even low-volume production runs. While I won't go into full details here, it involved using a manual or small power tool to wrap a few inches of stripped, thin wire seven times in a spiral around a skinny, square post and then connecting the other end of the wire to another post. These posts were extended pins of special sockets for ICs and passives, all mounted on a board.

![[Wirewrap 01 (cr)]](/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/04/Wirewrap_01_cr.jpg)

__Figure 1:__ *Wire wrapping*

The end result was seven wraps grabbing the four post corners, yielding 28 "gas-tight" connections. It was a labour-intensive but effective way to wire a board, as long as you paid attention to what you were doing: It was easy to get mentally numb and connect the wrong posts, or get sloppy and have little cut shards of wire and end-pieces short out adjacent pins.

Wire wrap has pretty much gone the way of the dinosaur in our industry, so to speak, and I am not going to praise it or lament its passing here. It had its time and its time has passed, as the copper-clad and etched PC board, high-density circuits, and higher frequencies became the norm. Wire wrap simply could not compete in that arena.

But dealing with wire wrap taught me, once again, that it is so easy to assume and be wrong. What was my misassumption about wire wrap? Simple: Based on my personal experience with breadboarding circuits, I was sure that wrapping a wire around a post simply could not be a reliable technique. In my world, you soldered wires, you crimped them, or you screwed them to a terminal if you wanted a solid connection. Anything less was asking for trouble.

Of course, my curiosity about wire wrap and its presumed unreliability led me to do some research. It turned out that extensive testing by the reliability experts at Western Electric (the manufacturing arm of AT&T, back in the day when AT&T was the one-and-only "phone system") showed that it was an extremely reliable method, if done correctly (it was even used for the Apollo guidance computer). Admittedly, that was a big "if" for a novice wrapper like me and many around me, but I figured if the guys who designed and tested standard phone handsets for a 40-year operating life said it was OK, then it must be OK, no need for me to worry.

Once again, my initial assumption, based solely on personal experience, led me prematurely to a wrong conclusion. Each time that happens, I say it won’t happen again. But it's human nature to jump to conclusions even before the evidence is in, or perhaps there is no time to do any checking.

Have you ever held opinions based primarily on your own experience and supposition that turned out to be wrong? If so, how did you find out? What happened when you did?

This article first appeared on EE Times U.S.