Blog: Huawei, On the Road to Recovery?

Article By : Lou Hoffman

PR pro Lou Hoffman diagnoses Huawei's communications problems, and recommends a regimen for digging itself out of its current crisis.

Huawei has historically done a poor job engaging with markets. PR pro Lou Hoffman diagnoses Huawei's communications problems, and recommends a regimen for digging itself out of its current crisis.

“Beset with difficulties” doesn’t quite capture what Huawei is experiencing these days. “Beleaguered” is the word that seems tethered to the communications giant.

As a student of communications — the type with words, not satellites — I’ve been observing Huawei from afar since China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. Founder and CEO Ren Zhengfei shuns the spotlight the way Howard Hughes once did. That the company rolled him out to talk with journalists last month tells us Huawei is aware it’s in a crisis.

Is Huawei making the right moves to manage its reputation? What else should Huawei be doing from a PR perspective? Answering these questions calls for a look at how Huawei has handled communications in the past. To borrow a cliché, it’s complicated, with enough gradations of gray to fill Escher’s lithograph “Relativity.”

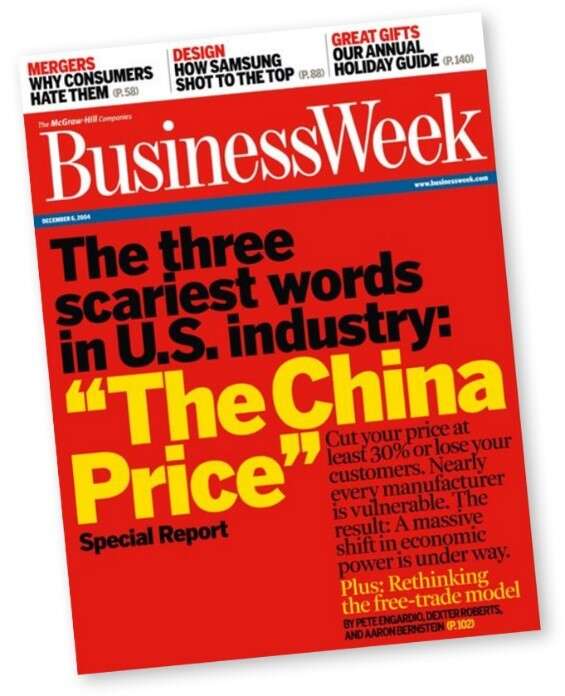

Let’s start by taking into account how the West and the U.S. perceive China. It’s easy to fall into the trap  of thinking that the Trump Administration invented anti-China rhetoric. Negative characterization of Chinese business goes back years. A BusinessWeek cover from 2004 trumpeted the headline, “The three scariest words in U.S. industry: The China Price.” And just to be sure no one missed the point, the cover included the passage, “Cut your price at least 30% or lose your customers. Nearly every manufacturer is vulnerable.”

of thinking that the Trump Administration invented anti-China rhetoric. Negative characterization of Chinese business goes back years. A BusinessWeek cover from 2004 trumpeted the headline, “The three scariest words in U.S. industry: The China Price.” And just to be sure no one missed the point, the cover included the passage, “Cut your price at least 30% or lose your customers. Nearly every manufacturer is vulnerable.”

A Congressional Report from 2012 formally went after Huawei (and ZTE) as untrustworthy, an event that triggered a “60 Minutes” exposé and further trashing of the company’s reputation. As far back as 2001, the National Counterintelligence Agency was warning the House and Senate Intelligence Committees that if Huawei equipment underpinned 4G networks in the U.S., every cell tower could serve as a potential listening post for the Chinese government.

This history is important because Huawei must take into account how the United States perceives China. It’s an art, calibrating the right level of aggressiveness to challenge an unfair characterization without hurting the cause, and without coming off as, “I believe the woman doth protest too much.”

That said, there’s not much calibration that can be done on something that’s barely there. With its historical reluctance to communicate, Huawei bears some responsibility for the negative perceptions of the company.

Recommended

Blog: The Reality of Rejecting Huawei

**Reputation by the numbers**

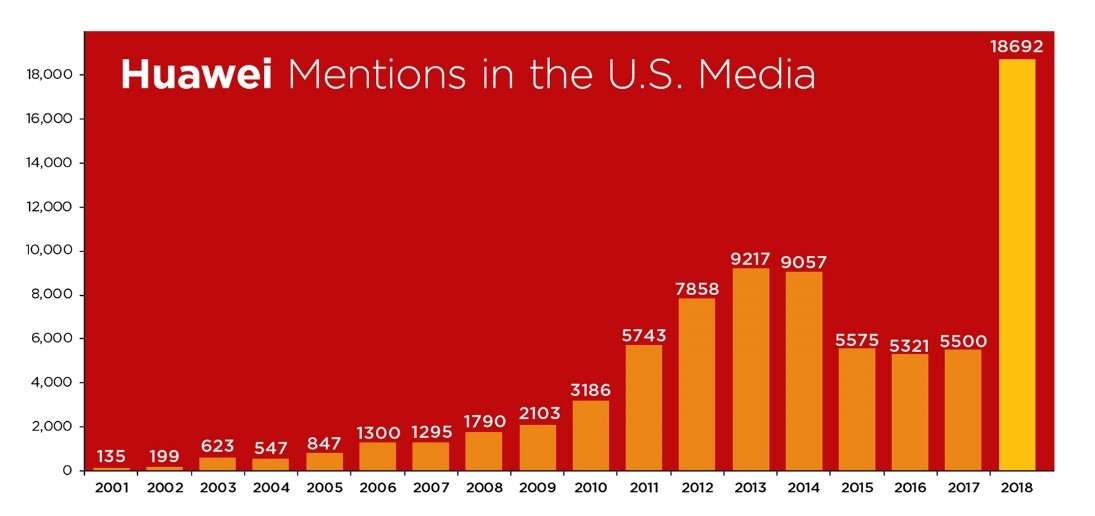

The chart below shows the number of stories that include the word “Huawei” from the U.S. Factiva database going back to 2001 when China joined the WTO.

The modest numbers for such an extended period of time show a company that didn’t invest in communications. By 2011 Huawei was generating over $30 billion in revenue with a huge chunk coming from international markets, but communications in those markets was an afterthought. It wasn’t until that year that Huawei made its first hire of a senior PR executive with international experience who wasn’t Chinese to look after communications outside of China.

I also think the modest numbers reflect a U.S. media that can be disinterested in Chinese companies. If an American startup secured over $100 million in venture funding, stories on the transaction would flood our news feeds. Yet when a Chinese startup in the high-profile self-driving car sector landed over $100 million in venture funding last year and distributed a news release, there isn’t peep from the U.S. media.

If we rewind the tape to 2005, Huawei already had over $2 billion in revenue and was dislodging legacy players in major accounts, but still had only 847 mentions, and we don’t know how many stories focused on Huawei and how many were throw-away mentions. Nor do we know how the sentiment of these articles breaks down.

To put those numbers into context, consider that Cisco generated 40,243 hits in the same Factiva U.S. database in 2005, meaning Huawei’s U.S. media footprint was around 2 percent of Cisco’s. Lack of proactive PR from Huawei alone doesn’t explain such a massive disparity.

That Huawei began catching up wasn’t necessarily a good thing. Journalists like a “train wreck,” which explains why the numbers spike in 2012 thru 2014. That’s when the House Intelligence Committee issued its report warning everyone that Huawei and ZTE pose a threat to national security. The result was a wave of negative media coverage, including the aforementioned “60 Minutes” broadcast. The spike in the chart in 2018 featured more Huawei drama that reenergized journalists, and brings us to today.

When a company is navigating a crisis like the one Huawei faces — attacks from multiple flanks: the U.S., Poland, the UK, Australia, etc. — the CEO represents one of the most effective “tools” if not THE most effective way to insert the company’s voice in the discourse and diffuse the claims. As noted earlier, Huawei recognizes the power of the title and had its CEO headline several media functions last month.

The Straw CEO

The problem is that if the only time a CEO talks with journalists is during a time of crisis, the title forfeits much of its power in shaping public perception. Journalists don’t know the exec. The public doesn’t trust the exec. There’s no equity in the karma bank.

As best as I can piece it together, Ren was incognito from the time he founded the company until 2013. It wasn’t until Huawei was under U.S. congressional attack that he decided it was time to talk to the press. He sat down with a handful of journalists in New Zealand.

I can understand the Huawei PR team wanting to give the big boss a soft landing and knowing he might be a bit rusty, but Wellington, New Zealand? Sure, they got the headline they wanted in the New Zealand Herald, “Huawei Founder Scoffs at US Rage,” and, yes, international media syndicated the story — no doubt part of the master plan — since it was the first Ren sighting in 26 years, but what did they really accomplish in terms of moving the perception needle in the U.S. and in the West?

I’d say they accomplished nothing except making sure that Ren didn’t face any tough questions from pesky reporters from countries where the charges against Huawei originated.

Yet, Ren’s recent engagement with the media doesn’t have to be for naught if it’s the start of regular interactions with the media — a good segue to address how Huawei’s communications can help the company rebuild its reputation going forward.

First, the company needs to think long-term. The goal isn’t to weather the current storm. The goal is to show the world outside of China that Huawei is a good global citizen and a company that you can trust. This is going to take years, not months.

Talking is only half of it, of course. If the company isn’t behaving like a good global citizen and taking actions that show it’s trustworthy, then communications becomes nothing but spin.

To ensure that behavior aligns with aspirations, I would appoint an individual to the Huawei Board of Directors who has international communications experience and is from the West. All 17 current Huawei Board members are Chinese. Given the stakes for the company in the West and the billions of dollars in revenue directly tied to reputation, having one Board member who can represent this point of view seems advantageous. Plus, it ensures there’s at least one person with a seat at the table to champion communications.

People don’t trust what they don’t know. The first step for Huawei to start earning trust is to offer journalists, analysts and other influencers consistent access to Huawei executives, month after month after month, not just when the company is experiencing a rough patch. It will take time and money, and even after doing it, Huawei is still going to take some punches. That goes with the territory of being one of the more influential tech companies in the world.

This idea of accessibility must apply to Ren. I would fly him to the U.S. twice a year to engage with the media, once to New York and once to Silicon Valley. This type of activity more than anything else would send a clear message to the market that Huawei acknowledges it’s not business as usual and it needs to provide a deeper window into the company.

I would also have Ren offer a monthly point of view published on Medium, the platform many U.S. executives have used to accentuate their perspectives, most recently Jeff Bezos taking on the parent company of The National Enquirer for extortion. What’s critical for Huawei is that the thinking for these monthly essays needs to come from Ren himself. Collectively, they will help the outside world understand how he manages and leads Huawei. Plus, journalists aren’t starting at ground zero when they meet with him on a semi-annual basis.

Recommended

Blog: Huawei’s Pattern of Deceit

**Get Proactive**

Now comes the toughest one: claims that the Chinese government can commandeer Huawei’s equipment to access private information and for spying. This issue is above my pay grade, but it seems like a third-party audit or analysis would help alleviate this concern. While it’s not exactly apples to apples, how Supermicro (disclosure, a client) responded to the Bloomberg story, “The Big Hack: How China Used a Tiny Chip to Infiltrate U.S. Companies,” offers a potential playbook. Supermicro hired a third-party investigations firm that conducted an audit and turned up no evidence of malicious hardware, essentially diffusing the story.

As for what happens when the Chinese government asks Huawei for information or access due to “national security concerns,” Huawei has said the right things. Time will tell. As Junko pointed out in "Huawei's Media Mess," her recent opinion piece on Huawei, “…. The Chinese Communist Party’s stranglehold on Huawei makes it hard for anyone in the West to determine whether they’re dealing with a private company or an agent of Beijing.”

Any change at Huawei has to come from the top. A South China Morning Post story last month included this Kodak moment: “Ren admitted that he was ‘forced’ by Huawei’s public relations team to agree to the interviews as the company was in a ‘transitional stage’ of the current crisis …”

Huawei has built a strong internal PR team with senior international pros who know their stuff. No doubt, they’ve presented some (all?) of these ideas to the executive management team. I guarantee they’ve been banging the drum for greater access to the company and its executives for years. The problem is the big bosses who don’t have communications experience have the final vote. I suspect if Huawei’s management trusted the counsel of its senior PR team and executed accordingly, that alone would advance the public profile in a meaningful way.

Supply Side Communications

If the person at the top doesn’t value communications, the rest of the management team and employee base aren’t going to value communications either. That needs to change. The company should put together an internal program that explains to its 180,000 employees why outbound communications is important, how the company’s reputation impacts business success and its approach to communications. I would also develop a module on communications for the onboarding process of new employees. This won’t change the culture and mentality overnight. It’s a long-term play.

I invented the word “Americanitis” to describe how U.S. executives often think that having a high profile in their home market automatically guarantees a hero’s welcome when they land on foreign shores. Such a mentality can lead to frustration and slow down the building of the company’s brand in new markets. I suspect that Huawei has suffered a version of this.

Look, this is a tough one. It’s like playing three-dimensional chess right after waking up in the morning … and you enjoyed one too many margaritas the night before. So many variables to contend with and not all of them of the logical variety.

Stripping away the complexity brings us back to the point that a new era for communications at Huawei has nothing to do with communications. It has everything to do with the behavior and actions of the CEO and the management team. If they don’t get this right, none of the other stuff matters.